Jay Michael Arnold – Lecture Notes for Introduction to Philosophy

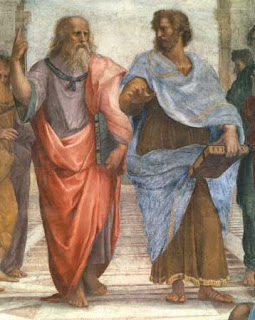

Plato & The Theory of Forms

Plato (427-347BCE)

Plato was a student of Socrates and present at his trial and execution. He founded a school, the Academy in Athens, considered by many the first European university. He wrote many philosophical dialogues wherein he used the character of his teacher Socrates to investigate philosophical questions. Among his works is the Republic, widely considered one of the foundational texts of Western thought and culture. When Plato died in 347, his student Aristotle continued his legacy, albeit disagreeing with Plato and offering a critique of his ideas.

Plato’s Reaction to Protagorus & Heraclitus

Plato’s Theory of Forms was a reaction to earlier Greek philosophers with whom he disagreed, especially his predecessors Protagorus and Heraclitus.

The philosopher Protagorus was famous for saying, “Man is the measure of all things”. What Protagorus meant was that each individual person is her own criterion for truth; that is, whatever you perceive as true or false is true or false; and whatever you think is good or bad is good or bad. In short, there is no universally existing thing, no universal right or wrong, or good or bad that is true for everyone. For example, if you think that stealing is morally right, then it is right- even if others disagree with you. A person is not accountable to a higher authority or universal law (like the Ten Commandments).

“This is often called, relativism or subjectivism because it makes the most important things relative to and dependent upon the individual (or community, society, etc.), or because it asserts that the subject (either an individual, community, society, etc.), is the source and standard of being, truth and goodness.” (Miller 71)

The Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus was famous for saying, “The sun is new everyday” and “We are and we are not” by which he meant that reality is always changing and nothing remains the same. Reality, according to Heraclitus, is dynamic and always in flux. Everything is constantly changing, nothing stands still for a moment, the world and everything in it is in a ceaseless movement, activity, coming and going, ebbing and flowing. In fact, his slogan “All things flow” suggested that the ever-changing universe was like a river, and according to Heraclitus “You cannot step twice into the same river” meaning that once you put your other foot down to step into the flowing water, it’s a different river.

Plato’s Distinction Between ‘Being’ & ‘Becoming’

Plato disagreed with both Protagorus and Heraclitus.

Plato rejected Protagorus’ relativism, claiming instead that if individuals were the standard for right and wrong then all discussion of justice, blame, praiseworthiness, virtue, and moral responsibility was meaningless. How can we even discuss right and wrong if it’s different for every person? According to Plato, if our notions of being, truth, goodness and morality are to be meaningful, then they must be anchored in some objective (exists outside our own minds), independent (not dependent upon anything else for its existence), and absolute (unchanging) Reality. There must exist, then, another world beyond this world and above our minds- a world of Being. Plato had three goals that he desired his philosophy to fulfill:

Plato's Three Metaphysical Objectives

1.) Objective (exists outside our own minds)

2.) Independent (not dependent upon anything else for its existence)

3.) Absolute (unchanging)

Plato rejected Heraclitus’ theory of an ever-changing reality, claiming instead that there must be something about this changing world that doesn’t change, something reality beyond the sensible world of multiplicity and change. Plato admits that the sensible world is always changing, always Becoming; however, he thinks there is another reality that makes this constant Becoming possible, namely, the world of Being.

On pp. 174-175 of Republic, (Book V 479c-end) Plato draws the distinction between the two worlds: the world of Becoming and the world of Being, and the corresponding difference between knowledge and opinion. In this passage Plato represents the world of Becoming as a ‘twilight zone’ or ‘half-way region’ between reality and unreality.

The distinction between the world of Being and the world of Becoming is further delineated in the following passage from Plato’s Timaeus:

“…We must make a distinction and ask, ‘what is that which always is and has no becoming, and what is that which is always becoming and never is? That which is apprehended by intelligence and reason is always in the same state, but that which is conceived by opinion with the help of sensation and without reason is always in a process of becoming and perishing and never really is.” (Timaeus, 27d-28a)

Thus, Plato believes that reality is made up of the sensible world of Becoming and the transcendent (beyond space and time) world of Being. The world of Becoming is always changing; while the world of Being never changes.

Plato’s World of Being, or the Forms

The next step in understanding Plato’s Theory of Forms is to grasp that for Plato the transcendent world of Being is populated by realities called Forms. According to Plato, Forms in the world of Being are the causes of the particular things in the world of Becoming. For example, there is a Form of TABLE in the transcendent world of Being that causes particular things in the world of Becoming to appear as tables. As we all know, tables come in many shapes, sizes, colors and designs- but all of them have in common the fact that we consider them to be tables. All tables, no matter how different from each other they may be, have an undeniable ‘tableness’. That transcendent quality of ‘tableness’ that all tables share is the Form of TABLE.

Six Characteristics of Forms

1. Objective – They exist “out there” as objects, independently of our minds or wills.

2. Transcendent – Though they exists “out there,” they do not exist in space and time; they lie, as it were, above or beyond space and time

3. Eternal – As transcendent realities they are not subject to time and therefore not subject to motion or change

4. Intelligible – As transcendent realities they cannot be grasped by the senses but only by the intellect

5. Archetypal – They are the models of every kind of thing that does or could exist

6. Perfect – They include absolutely and perfectly all the features of the things of which they are models

The Relationship Between Forms and Particular Things

Definition: “The Theory of Forms is the belief in a transcendent world of eternal and absolute beings, corresponding to every kind of thing that there is, and causing in particular things* their essential nature.” (Miller, 76)

*From now on I will refer to “particular things” simply as “Particulars”

CHART: Relationship Between Forms and Particulars

FORMS in the world of Being PARTICULARS in the world of Becoming

Transcendent Spatial-temporal

Eternal Changeable

Intelligible Sensible

Archetypal Copied

Perfect Imperfect

World of BEING World of BECOMING

TABLE this table here, that table there, etc.

JUSTICE Nuremburg Trials, Civil Rights Act, etc.

STUDENT Bob, Sally, Brad, Kristy, etc.

According to Plato, Particulars have an essence or nature because they stand in relation to their Form. But what exactly is the relationship between a Particular and its Form? Plato was troubled by this question and offered only a vague explanation:

“[Plato] talks as if sensible things are copies or imitations of the Forms, and at other times he talks of a participation of the sensible thing in its Form. Thus a table is table because it imperfectly reflects or is an imperfect copy of its pattern or model, the Form Tableness, or it is a table because it participates in the Form Tableness.” (Miller, 78)

Later, Plato’s star pupil Aristotle will criticize his teacher for not being more precise.

In further delineating the relationship between Forms and Particulars, Plato pointed out two important issues:

(1) Particulars can participate in more than one Form. For example, an apple (Particular) can participate in more than one Form, like Redness, Hardness, Sweetness, etc, and

(2) (2) a Particular can exhibit characteristics that are not necessarily part of its nature. For example, ink does not have to be blue in order to be ink. It can be red, black, etc. It’s the same with an apple. An apple doesn’t have to be red to be an apple; it can be green. And it doesn’t have to be sweet; it can be sour and tart.

Plato’s Divided Line

Metaphysics Epistemology

Higher Forms Understanding

BEING KNOWLEDGE

Mathematical Forms Reason

Sensible Objects Perception

BECOMING OPINION

Images Imagination

The Essential Form of the Good

For Plato, there exists something beyond the Forms, something from which the lower and higher forms derive their being. “And just as it is above all a reality, and is their ultimate source, so it is above all knowledge and is its ultimate source.” (Miller 83)

Plato calls this “the essential Form of the Good”. He compares this essential Form of the Good to the sun, by which we perceive all things and by which all things have their existence, or survival. “The Good is to the intelligible world, or world of Being, as the sun is to the visible world, or world of becoming.” (Miller 83)

Plato & Aristotle on the Soul

According to Plato, the soul remembers the forms from a previous lifetime. The soul recognizes the forms by remembering them, like when you run into an old friend on the street.

According to Aristotle, the soul knows the forms through rational intuition. The soul does not remember, rather, the soul intuits knowledge of the forms.

No comments:

Post a Comment